By Edie Parnum

Every year we feature two superior native plant species. One of the Prime Plants for Nature is a tree, shrub, or vine and the other is a perennial. Prime Plants are selected based on these criteria:

- Native to southeastern Pennsylvania

- Offer high wildlife value and contribute significantly to your property’s web of life

- Provide food for wildlife by producing nutritious fruits, seeds, nuts, nectar, or pollen

- Most host insects that are eaten by birds or other animals

- Offer shelter and places to raise young

- Easy to grow and make an attractive addition to your landscape

- Sold at native plant nurseries and native plant sales. (See list of local sources for native plants at the end).

Our selections for the 2019 Prime Plants for Nature awards are:

Amelanchier canadensis, Serviceberry (also known as Juneberry or Shadbush) A. arborea and A. laevis are closely related species.

Berries on Serviceberry ripen in early summer and are quickly eaten by birds. © Mark Gormel Click to enlarge.

Wildlife Value: In the early summer this small tree produces berries relished by American Robins, Gray Catbirds, Cedar Waxwings, and Northern Mockingbirds. Other birds and mammals eat the fruits as well. The popular fruits disappear quickly, often before they are completely ripe. The foliage of Serviceberry is food for 124 species of caterpillars including Striped Hairstreak and Red-spotted Purple butterflies and Blinded Sphinx and Small-eyed Sphinx moths. The nectar-rich flowers attract adult butterflies, bees, hummingbirds, and other pollinators.

Cedar Waxwing eating Serviceberry fruits. © Harris Brown. Click to enlarge.

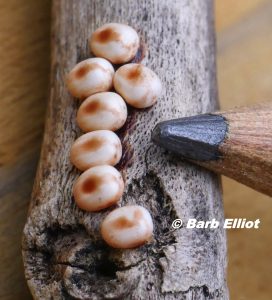

Serviceberry is a host plant for Red-spotted Purple butterfly caterpillars. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Growing Conditions: Serviceberry is easily grown in sun or part shade. It prefers moist soil, but will tolerate a variety of conditions. Although sometimes subject to rust or leaf spot, it is normally free of any severe problems. Rust (Apple Cedar rust) can be a problem for anyone who also has nearby Eastern Red Cedar. It is moderately deer-resistant.

Serviceberry blooms profuely in April. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Appearance: A single-trunk or multi-stemmed tree, Serviceberry grows to 15-25 feet at maturity. This member of the rose family is covered with showy white blossoms in early spring before the foliage emerges. The

Blossoms of Serviceberry are popular with native bees and other pollinators. © Barb Elliot. click to enlarge.

attractive fall foliage is yellow to orange-red. Amelanchier canadensis, A. arborea, and A. laevis are closely related species that hybridize and are difficult to differentiate unless you are a

botanist.

The Serviceberry should not be confused with Bradford Pear, also known as Callery Pear, an invasive tree with similar white flowers that blooms at the same time. The Bradford Pear has upright branches and denser, dark foliage. It out-competes native species, hosts very few native insects, and produces fruit that is unpalatable to birds and other wildlife. For more info about invasive Bradford/Callery Pear in Pennsylvania, click here.

Garden Phlox, Phlox paniculata

Giant Swallowtail, a rare butterfly in southeastern PA, visited my Garden Phlox. © Edie parnum. Click to enlarge.

Wildlife Value: Garden Phlox is a nectar-rich perennial that attracts native pollinators including butterflies, bees, moths, and hummingbirds. The flower petals are fused into a tube (corolla). To access the nectar, a pollinator inserts its tongue (proboscis) into the bottom of the corolla.

Bumble bee nectaring at Garden Phlox. © Bonnie Witmer. Click to enlarge.

Butterflies and large bees with a long proboscis and hummingbirds can reach the nectar. Small bees such as Sweat Bees, Yellow-faced Bees, Leafcutter Bees, and small carpenter bees have a proboscis that is too short to reach the nectar. However, all will pick up pollen as they rub against the anther (male part) at the top of the corolla. Flying from flower to flower, these pollinators carry the pollen to the stigma (female flower part) of each bloom. As a result, reproduction occurs.

Among the insect pollinators using Garden Phlox, Hummingbird

A moth with transparent wings, a Hummingbird Clearwing, nectars on Garden Phlox. © Tony Nastase. Click to enlarge.

Clearwing Moth is a conspicuous day-flying sphinx moth that is sometimes mistaken for a hummingbird. Also look for Peck’s Skipper, a small tan butterfly.

Growing Conditions: Garden Phlox will grow well in sun or part sun in moist to average (tolerates clay) soil.

Appearance: The pink, lavender, or white flowers bloom profusely in late summer and early fall on 3-4-foot plants. Many cultivars (often referred to as navitars) are

Tiger Swallowtail butterfly on Garden Phlox. © Edie Parnum. Click to enlarge.

available, but some have reduced nectar production. However, according to studies performed at Mt. Cuba Center, ‘Jeana’ produces nectar abundantly and attracts many pollinators. Garden Phlox can develop mildew during hot, humid summer conditions. Removing some of the flower stalks will improve air circulation and prevent mildew. According to Mt Cuba, the ‘Jeana”, ‘Robert Poore’, and ‘David’ cultivars are mildew-resistant.

Other phlox species: Woodland Phlox, Phlox divaricata, and Creeping Phlox, P. stolonifera, are spring-blooming phlox species that grow in part shade or shade. They attract a variety of pollinators including butterflies and hummingbirds. The flower structure is similar to Garden Phlox.

——————————————————————————————

Local Sources of Native Plants

Bowman’s Hill Wildflower Preserve, 1635 River Rd. New Hope, PA 18938. 215-862-2924 or bhwp.org. Nursery open April -October.

Collins Nursery, 773 Roslyn Avenue, Glenside, PA 19038. Native trees, shrubs, and some perennials. Spring and fall open houses. Otherwise appointment necessary. 215-715-3439 or collinsnursery.com.

David Brothers Native Plant Nursery, Whitehall Road, Norristown, PA 19403. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. 610-584-1550 or davidbrothers.com

Edge of the Woods Nursery, 2415 Route 100, Orefield, PA 18069. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. 610-393-2570 or edgeofthewoodsnursery.com.

Gateway Garden Center, 7277 Lancaster Pike, Hockessin, DE 19707. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. 302-239-2727 or gatewaygardens.com.

Gino’s Nursery, 2237 Second Street Pike, Newtown, PA 18940. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. 267-750-9042 or ginosnursery.com.

Good Host Plants, 150 W. Butler St., Philadelphia 19140. Straight species native perennials and woody plants of local genetic provenance. 267-270-5036 or goodhostplants.com.

Jenkins Arboretum, 631 Berwyn Baptist Road, Devon, PA 19333. 610-647-8870 or jenkinsarboretum.org. Outdoor plant shop open daily 9-4 late April through mid-October.

Northeast Natives Perennials, 1716 E. Sawmill road, Quakertown, PA 18951. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. 215-901-5552 or nenativesandperennials.com

Redbud Native Plant Nursery, 904 N. Providence Road., Media, PA. 19063. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. 610-892-2833 or redbudnativeplantnursery.com.

Yellow Springs Farm, 1165 Yellow Springs Road, Chester Springs, PA 19425. Native trees, shrubs, and perennials. Landscape design and consultation services available. Spring and fall open houses. On-line and phone orders available. Otherwise call for appointment. 610-827-2014 or yellowspringsfarm.com

Native Plant Sales

Bartram’s Garden, 5400 Lindbergh Boulevard, Philadelphia, PA 19143. 215-729-5281 or bartramsgarden.org.

Brandywine Conservancy, Routes 1 and 100, P.O. Box 141, Chadds Ford, PA 19317. 610-388-2700 or brandywine.org/conservancy. Mother’s Day weekend. Seeds also available.

Delaware Nature Society, Cloverdale Farm Preserve, 543 Way Road, Greenville, DE 19807. 302-239-2334 or delawarenaturesociety.org. First weekend in May.

Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust, 2955 Edge Hill Road, Huntington Valley, PA 19006. 215-657-0830 or pennypacktrust.org.

Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, 8480 Hagys Mill Rd., Philadelphia 19128. 215-482-7300 or schuylkillcenter.org.