By Barb Elliot

OK. I’ll confess. I love bats! Fifteen years ago my father and I built a bat house for them. Each spring, I watch expectantly for “my” bats to return to their bat house. And, every spring they have come back. I always breathe a sigh of relief.

Barb’s pole-mounted rocket-style bat box awaits the spring return of “her” bats. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Through summer and early fall I watch them at dusk. I thrill to see two or three flying in large circles over my yard. Watching them swerve and swoop, I marvel as they deftly capture night-flying insects. Using echolocation — emitting sound waves that bounce off objects and echo back to them — they successfully locate, catch and consume mosquitoes, moths, and beetles that fly in the dark. Each night they eat half their body weight (lactating females eat 100% their body weight) in insects– as many as 1,000 insects an hour! Mosquitoes are not a problem in my yard. By eating insect pests, bats offer their services to farmers, too. Farmers can use fewer pesticides and save money. Consequently, our food costs are lower, and an added benefit, pesticides are kept off our food and out of the environment.

Nine species of bats, all insect-eaters, live in Pennsylvania. Three species (Hoary, Red, and Silver-haired) migrate south in the fall, to find insects. The other six species, including “my” Big Brown Bats, head to caves or mines (known as hibernacula) where they hibernate until insects become plentiful again in the spring. In the cold, constant temperature of a hibernaculum the bats roost huddled together in groups. They enter a state of torpor, lowering their body temperatures (from 108 degrees to 39 – 59 degrees F). Their heart rates slow (from 1000 beats per minute to 10 bpm) to conserve energy and they live off their fat stores. Every three weeks, the bats rouse themselves. Their body temperatures and heart rates rise briefly to normal summer rates before returning to their state of torpor.

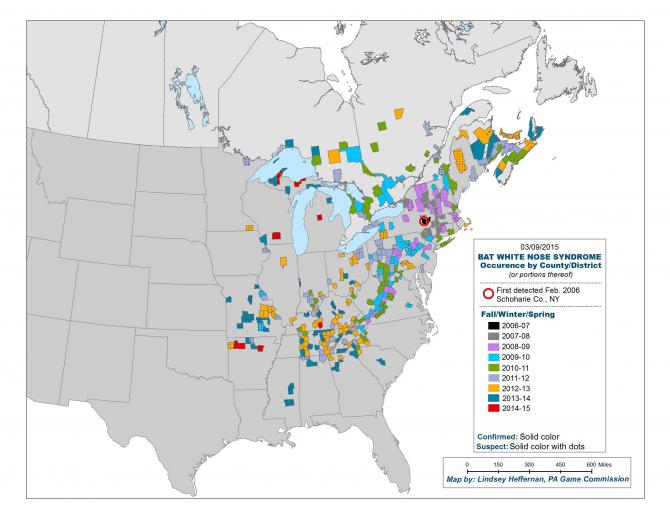

Hibernating bats are dying in droves. In 2006, a cold-loving fungus from Europe

(Pseudogymnoascus destructans) was found in bats in four caverns in upstate New York. This fungus, which thrives in the cold of caves and mines, causes a disease in bats known as White-nose Syndrome (WNS). WNS is fatal and has decimated bat populations. It damages bats’ muscles, connective tissues, and skin, and causes them to rouse more frequently (every 5 days vs. every 3 weeks). Their fat stores are depleted during the winter, Death occurs well before spring.

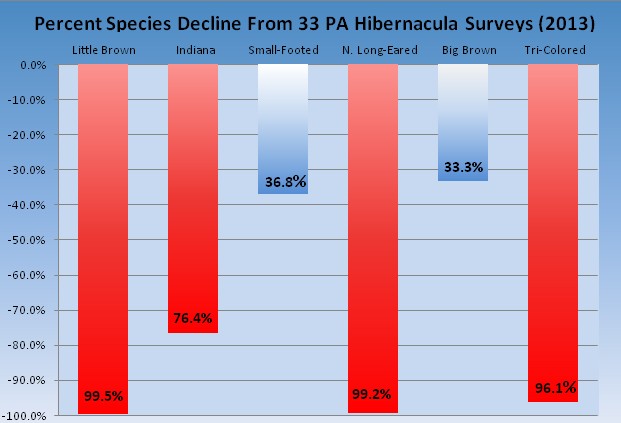

White-nose syndrome has spread rapidly. Confirmed in PA in winter 2008-2009, it is now in 25 states and 5 Canadian provinces. The disease has killed over 95% of bats at every wintering site. (See chart for the heartbreaking declines of our PA bats.) PA has lost

more bats than any other state. Hibernacula that previously held tens of thousands of bats now hold just a few hundred or fewer. Overall, PA has lost over 99% of its total bat population because the largest die-off has been in Little Brown Bats, formerly the most populous PA species.

WNS has killed over 5.7 million bats — the worst disease to affect North American wildlife

March, 2015 map from White-noseSyndrome.org showing spread of WNS to states and provinces. Click to open in separate window.

in centuries. It continues its deadly march. Scientists at many laboratories and federal and state agencies are investigating ways to control WNS and protect bats. If a solution is found, it could still take hundreds of years for some bat species to return to pre-WNS levels. After all, most bat species have just one or two pups a year.

Red Bat with 3 pups, though most bat species have just 1 or 2 pups a year. Wikimedia Commons image by Josh Henderson. Click to enlarge.

WNS is a daunting disease, but there are things you can do to help bats:

- Build a bat house for roosting bats. Bats are particular about their roosts, so do a little research to understand their housing needs and location preferences. See Install a Bat House for detailed guidelines.

- Contribute toward WNS research by donating to Bat Conservation International (BCI) and consider becoming a member of BCI.

- Participate in the Appalachian Bat Count project in PA by counting bats at a maternity colony in the summer. These counts are especially important because of WNS.

- If a bat strays into your home, don’t harm or try to catch it. Simply open a door or windows. After it gets its bearings, the bat should leave within 10 or 15 minutes.

- If a colony of bats moves into your attic, take measures to exclude the bats only after mid-July when pups are able to fly. If possible, provide an alternate roost as a new home for the colony. See Bats in Buildings: A Guide to Safe and Humane Exclusions or Penn State Extension’s bat exclusion and alternate roost information.

- Learn more about bats and White-nose Syndrome and share your knowledge with family, friends, and neighbors.

This spring, I’ll be waiting and watching for “my bats” to return to my bat house. I hope they’ll have survived White-nose Syndrome once again. Look for bats in your

A healthy hibernating Big Brown Bat., Wikimedia Commons Image by Ann Froschauer, USFWS. Click to enlarge.

neighborhood, too. Please join me as an advocate for these often misunderstood, but extremely valuable creatures.

Resources:

Bat Conservation International

White-nose syndrome in Pa. bats could lead to endangered status, affect jobs. Rick Wills, Pittsburgh TribLive, December 15, 2012

Special thanks to Dan Mummert, Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Pennsylvania Game Commission, Southeast Region, for sharing his expertise and WNS data