By Barb Elliot

Monarch butterflies are on the move. I’ve been seeing them fly through my yard, above fields, over traffic jams, through neighborhoods. These fragile creatures are heading southwest toward their ancient wintering grounds, stopping along the way to rest and sip nectar from late-blooming plants. The peak of Monarch migration through our area is mid- to late-September, but you may still see Monarchs if you spend time outdoors.

This generation of Monarchs is different from those we saw in the summer. Those Monarchs were intent on mating and laying eggs and only lived from two to six weeks. But this generation will live for about eight months and is in the midst of an epic journey. They will not mate, but instead are programmed to fly to a place they have never been before – mountains in Mexico where millions of Monarchs will roost together to survive the winter. Some of them will fly as far as 3,000 miles!

Migrating Monarchs depend on nectar sources along their route for energy to complete the journey. Next spring, the Monarchs that survive migration and the winter in Mexico will fly north into Texas, mate, lay eggs on milkweed plants and die. Caterpillars will hatch from the eggs, eat milkweed, change into chrysalises, and emerge as adult Monarch butterflies that in turn fly north, mate, lay eggs and die. The next generation will make its way farther north and east, repeat the cycle, and the U.S. and Canada east of the Rocky Mountains will once again be populated with Monarch butterflies during spring and summer. The great, great, grandchildren of the Monarchs that are now flying south will be the ones we see during their migration to Mexico next fall. Though some butterfly species complete a one-way migration, Monarchs are the only butterfly species in the world that accomplishes a two-way migration.

Migrating Monarchs face many threats, including bad weather, predators, and lack of food, but some have always survived to continue the species. However, if current

This Monarch, caught by a praying mantis, won’t make it to Mexico. Cape May, NJ, September 12, 2012 Photo © Barb Elliot

trends continue, we are in danger of losing Monarchs altogether. This year’s population, according to Chip Taylor, director of Monarch Watch, is about half the long-term average. Monarch numbers have been declining since the late 1990’s, but the downward trend has accelerated since 2003. Monarch Watch indicates the major cause for the decline is loss of food sources in the U.S. from development, routine mowing along roadsides, and the widespread use of herbicides that kill milkweed plants, the Monarch caterpillar’s only food. Increased use of genetically modified corn and soy crops on mid-west farms is likely responsible for much of the population decline. These crops are engineered to survive the spraying of herbicides which kill milkweeds and other plants growing in the fields. Since the year 2000, about 100 million acres of former Monarch milkweed habitat in agricultural areas have been lost in this way. The milkweed habitats that are left are not sufficient to sustain the larger Monarch populations of the 1990s.

This Monarch near Austin, Texas is much closer to the Mexican wintering grounds, but faces drought conditions with few flowers to provide nectar. October 9, 2012. Photo © Barb Elliot

Monarchs need our help! Monarch Watch has suggested a national effort to plant milkweeds in as many locations as possible, and have instituted a campaign called Bring Back the Monarchs. It’s not too late to get some milkweed started in your garden this fall, or you can wait till spring. Perhaps you can think of additional locations that milkweeds could be planted, such as in schoolyards, parks, business properties, or roadsides. Milkweeds do well in containers, too, so a large space is not necessary. Of the five species of native milkweeds in my yard, my favorite is Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). I found many Monarch eggs on my Swamp Milkweed this summer and also noticed that adults seemed to prefer the long-blooming Swamp Milkweed flowers’ nectar to that of other flowers in my yard.

You can help migrating Monarchs and other fall-flying butterflies by providing late-blooming nectar plants such as native asters and goldenrods. Consider adding flowering plants to your yard that provide a succession of blooms from spring through fall. You’ll be providing nectar not just for migrating Monarchs, but also for the Monarchs and other butterflies that fly earlier in the year. Check the native perennials on our Backyards for Nature plant list for some suggestions.

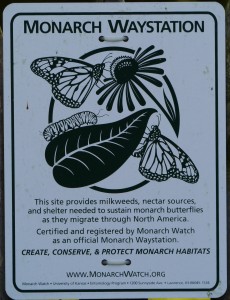

If you add milkweeds for Monarch caterpillars and nectar plants for the adults, you will be helping to make more Monarchs. You’ll not only have the satisfaction of knowing you’re helping to increase the population, but you’ll be able to see these marvelous butterflies in your yard and even witness their metamorphosis of egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly! You can also have your yard certified as a Monarch Waystation through Monarch Watch. This will mark your contribution to preserving Monarchs and show others how they, too, can help one of the true treasures of the natural world.

Below is a list of the locally native species of milkweed that I grow in my yard.

|

Locally Native Milkweed Plants** |

|||

| Botanical Name | Common Name | Bloom Color & Period | Light & Soil Conditions |

| Asclepias incarnata | Swamp Milkweed | Pink flowers; June & July | Part to full sun, moist soil |

| Asclepias tuberosa | Butterfly Milkweed | Orange flowers; June to August | Sun, dry to average soil |

| Asclepias verticillata | Whorled Milkweed | White flowers; July & August | Sun, dry to average soil |

| Asclepias purpurascens | Purple Milkweed | Dark pink/purple flowers; June & July | Part to full sun, dry/ average/moist soil |

| Asclepias syriaca* | Common Milkweed | Pink flowers; June & July | Sun, dry soil |

| *Spreads rapidly by underground rhizomes; best for large areas with other flowers and grasses | |||

| **All are deer resistant | |||

For a list of local nurseries that sell native milkweeds, click here.

For info on how to gather and plant milkweed seeds, click here.