By Barb Elliot

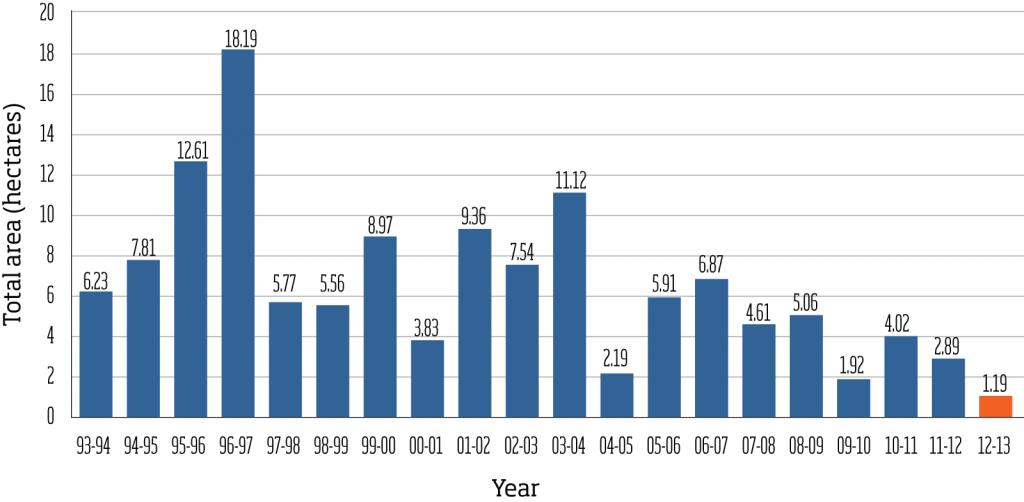

Distressed. That’s what we Monarch-lovers feel hearing the bad news about the butterflies overwintering in Mexico. Monarch numbers have fallen to dangerously

low levels – the lowest in the 20 years that records have been kept. This chart (based on area covered by wintering Monarchs) shows how the population has declined (1 hectare = 2.5 acres):

Source: Monarch Watch Caption: Chart from Monarch Watch http://monarchwatch.org/blog/2013/03/monarch-population-status-18

Reasons for the decline include recent weather extremes, but the most significant

factor is loss of Monarch habitat. In Mexico, much of the Oyamel fir forests that shelter wintering Monarchs have been lost. In the U.S. and Canada, millions of acres of farmland, roadsides, and undeveloped land that formerly provided milkweed, the Monarch caterpillars’ only food, have been lost. (See my October 13, 2012 post “Marvelous Migrating Monarchs Need Our Help” for more detail on the habitat loss).

We haven’t lost the Monarch yet. There is something YOU can do to help.

Male Monarch on New England Aster in Barb’s yard. September 21, 2012. Photo © Barb Elliot

Click to enlarge.

Chip Taylor, Director of Monarch Watch, says, “To assure a future for monarchs, conservation and restoration of milkweeds needs to become a national priority.”

To this end, Edie and I want to increase the number of host plants available in our area. We will be planting additional milkweeds in our yards, but we’d like to make it easy for you to join us in this endeavor. To encourage you to plant milkweeds we are offering three species of milkweed plants for sale at $1 per plant – less than our cost. These species are native to southeastern PA and are ones that we grow in our gardens. In addition to being host plants for Monarch caterpillars, they all have beautiful flowers that provide nectar and pollen for adult Monarchs and many other butterflies and pollinators. All are deer resistant.

These are the species we will be selling for $1 per plant:

- Monarch on Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) in Barb’s garden. July 9 2012. Photo © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

!!!!!!!!!!!!SOLD OUT!!!!!!!!!

Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata); pink flowers June to August; height 3-4’, spread 2’; part to full sun, average to moist soil; more sun results in more flowers, willow-like leaves 4-5” long

!!!!!!!!!!!!SOLD OUT!!!!!!!!!

| !!!!!!!!SOLD OUT!!!!!!!!!Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa); orange flowers June to August; height 18”-24”; spread 2’; sun, dry to average soil; tough, drought-tolerant, slow to emerge in spring, taproot makes established plants difficult to transplant; especially good for rock garden or dry slope | |

Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillata) in Barb’s yard. July 28, 2010. Photo © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!SOLD OUT!!!!!!!!!!!!

Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillata); white flowers in July and August; height 1-3’; spread 1-2’; sun, dry to average soil; fine-textured needle-like leaves

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!SOLD OUT!!!!!!!!!!!!

We need to know how many plants to order from our wholesale supplier, so we will be accepting your orders until Monday, April 1st. You may order as many as you like of each species. (Please note that Whorled Milkweed and Swamp Milkweed are both sold out and are no longer available. Butterfly Milkweed is still currently available.) You will be able to pick up your plants during the last week of May and/or the first week of June in the Wayne/King of Prussia, PA area. They will be hearty landscape plugs with well-developed root systems of about 5” deep. Our experience is that if planted in the right location, these plugs grow very quickly and mature enough to flower in their first year. We encourage you to plant at the very least 3, but preferably 8 or more of each species. With the plants about 12” apart, you can achieve a dense mass planting that will entice the butterflies with a showy target. When a female Monarch lays eggs on your milkweeds there will be enough foliage to sustain hungry caterpillars. If you don’t’ have enough space for in-ground planting, consider using pots or containers.

Monarch caterpillar on Swamp Milkweed in Barb’s garden. August 13, 2011. Photo © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

To order, send an email to this email address: info@backyardsfornature.org with Milkweed in the Subject line. Specify the quantity you want for each species and include your name. Again, the cost is $1 per plant. We will get back to you to confirm your order and let you know when and where you can pick up your plants. We plan to have flexible pick-up times in the Wayne/King of Prussia area after the plants become available, sometime during the last week of May/first week of June. We will let you know specific dates and location as soon as possible. Payment will be due at pickup.

Please pitch in to provide milkweeds to help the Monarchs! Talk to family, friends, and neighbors about the need. Share plants with them. When Monarchs return to the east in late spring, consider reporting your sightings as a citizen scientist by using http://www.learner.org/jnorth/ and/or having your yard certified as Monarch Waystation through Monarch Watch (www.monarchwatch.org). Check your milkweeds frequently for Monarch eggs and caterpillars. If you have the time, take some eggs or caterpillars inside to raise them. They will have a much better chance of survival and it’s fascinating and fun to do.

_______________________________________________________

For more information about Monarchs, their migration and raising them, scroll down to see my two previous Monarch-related posts of October 13, 2012 and August 20, 2012. Also, see:

http://monarchwatch.org/blog/2013/03/monarch-population-status-18/

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/16/opinion/the-dying-of-the-monarch-butterflies.html?_r=0