Cecropia Moth caterpillar in its last stage of development. July 2017. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

By Barb Elliot, Ph.D.

In July 2017, I came home from Mothapalooza, a conference for moth enthusiasts, with a Cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia) caterpillar. I was excited. The beautiful adult Cecropia (Hyalophora cecropia) is the largest moth in North America with a wingspan from 5″ – 7″. The showy caterpillars are chunky and grow to 4”- 4.5”. Although I had raised butterfly and moth caterpillars previously to increase their chances of survival, I now had the opportunity to observe the life cycle of this iconic silk moth and learn about its role in our ecosystem.

My caterpillar was almost full grown, but still had a voracious appetite. I kept it in a butterfly cage, provided a constant supply of fresh River Birch leaves, and removed the caterpillar waste (frass) each day. Cecropia caterpillars can eat other native tree and shrub leaves including elm, oak, maple, apple, cherry, ash, sassafras and willow, but prefer to stick to one kind once they begin eating. A Cecropia caterpillar gains more

than a thousand times its weight between hatching from its egg to being fully grown and ready to pupate and spin its cocoon.

In late summer, my caterpillar clung to a twig in the cage and spun a cocoon around itself. Inside the protective silk, it changed from a caterpillar to a dark brown pupa, the third stage in its development.

Many months later, on June 21, 2018, with metamorphosis complete, a spectacular female Cecropia moth emerged (eclosed) from the cocoon. With only a week to live and with no mouth parts to eat and drink, this adult female’s sole job was to mate and lay eggs.

I decided to keep the moth outside overnight to see if she could attract a mate. At dusk, I put her in a wire cage with holes sufficiently large for mating to occur. A male, with its large, feathery antennae, can detect the pheromones a female emits and hone in from over a mile away.

I got up at 5 AM the next morning to check on her. A male was clinging to the cage and mating with her! The two mated all day and de-coupled just before dark. Right away she began laying eggs. I released the male so he could mate with other females.

Mating Cecropia moths. Note the male’s (on right) larger, more feathery antennae. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

During the overnight hours, she laid about 130 eggs. After she rested, I released her so she could lay more eggs and live in the wild for the rest of her short life.

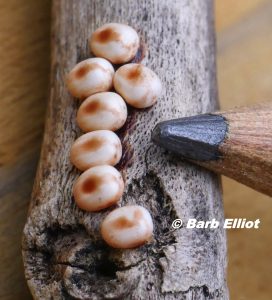

I kept five eggs and donated the rest to several environmental organizations and a few caterpillar-savvy friends. Three of my eggs hatched on July 4th, ten days after being laid.

My Cecropia eggs after three hatched. Note the two with exit holes chewed by the tiny caterpillars. July 4, 2018. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Each ¼” black, spiny caterpillar chewed a hole in its leathery brown egg and almost immediately began eating the River Birch leaves I provided. Within two or three days, the caterpillars outgrew the skin of their initial first stage (instar) and molted into a second instar. Each time a caterpillar molted, the new skin was “loose” so it could continue its rapid growth. All three ate, grew, and reached the fifth instar, their final caterpillar stage.

Newly hatched Cecropia moth caterpillar – first instar. . July 4, 2018. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Two Cecropia cats molting from 2nd to 3rd instar; one still in 2nd instar. 11 days old. July 15, 2018. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Two fifth instar Cecropias and one 4th instar. 31 days old. Aug 3 2018. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

While my Cecropias were growing, I got an opportunity to raise another large silk moth. On July 13, a friend noticed a large moth at the foot of a light pole – a Royal Walnut Moth or Regal Moth (Citheronia regalis). Unfortunately, the moth was dead but had laid eggs before succumbing. This hapless moth, like countless others, was drawn to nighttime outdoor lights, but was unable to escape the lights and died.

Of about 25 eggs I kept five and donated the rest to the Academy of Natural Sciences. Just one of mine hatched and I began feeding Black Walnut leaves, one of its host plants, to the tiny fierce-looking caterpillar. This caterpillar, known as the Hickory Horned Devil (HHD), is the largest caterpillar species in North America. This species also goes through five instars before pupating. Although harmless, each stage looks scary and unpalatable, intended to make a bird or other hungry predator steer clear of such a high-protein meal.

Early 5th instar of the Hickory Horned Devil. Aug 16, 2018. Day 24. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Hickory Horned Devil 5th instar, now greener with some blue near the head. Aug 19, 2018. Day 26. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Fifth instar, Hickory Horned Devil. Some blue starting in a few spots on top of body. Aug 22, 2018. Day 30.

Hickory Horned Devil in final 5th instar colors – ready to pupate. Wikipedia image by Chris Hibbard.

To my astonishment, I was raising the moth species with the largest caterpillar along with three caterpillars of the largest moth species. By the end of August, all three Cecropia caterpillars made their cocoons. My almost hotdog-sized HHD caterpillar turned into a dark brown pupa during the first week of September. This species doesn’t spin a cocoon like its Cecropia relative, but digs down into the soil to pupate and spend the winter. To simulate an underground environment. I provided an enclosure filled with crumpled paper towels, and the caterpillar pupated there successfully. When temperatures turned frigid, I moved the HHD pupa into my refrigerator for safe-keeping over the winter. As I had with their mother, I kept the Cecropia cocoons outside and waited for spring.

All three Cecropia moths eclosed – a male on May 22nd, and females on June 22nd and 25th – and I released them after dark on those nights.

The second of my 3 Cecropias to eclose from its cocoon – a female on June 22, 2019. © Barb Elliot. Click to enlarge.

Unfortunately, the HHD pupa died, so that huge, spectacular caterpillar didn’t become a beautiful Royal Walnut Moth as I had hoped. In nature, less than 5% of caterpillars survive to become butterflies or moths.

Because they are active only at night, it’s rare for us to see Cecropia, Royal Walnut, or other large moths. However, they and their caterpillars are key food sources for birds and other animals and thus are important members of our local food webs. You can help keep them flying by providing native trees and shrubs that caterpillars need for food. If you have outdoor lights, use timers or motion detectors so they are not on from dusk to dawn. Of course, don’t use pesticides, which kill not just moths and caterpillars, but other beneficial insects, many of which are in steep decline. If you’d like to see these and other interesting moth species, attend a local moth night event, perhaps during National Moth Week in July, or have a moth night of your own. I wish for you a Cecropia Moth, Royal Walnut Moth, and other magnificent nighttime moth wonders!